----

目次

序章 六本木ヒルズ

第一章 武人の風雪

第二章 西国の風雲

第三章 二人の歳月

断章 山川草木・旅順紀行

第四章 旅順という山塊

終章 戦いすんで

あとがき

----

序章 六本木ヒルズ

麻布上屋敷

六本木ヒルズという東京の街は、未来都市の模型を突然ここに持ってきて据えたような集落である。銀色の壁面をまぶしく湾曲させた、五十四階建ての巨大な森タワーが丘の上にそびえ、その周辺に、四十階建てのレジデンスと呼ばれる高級マンションをはじめ高層建築の群れが林立して、遠近法で描いたビュッフェの絵のような垂直の景観をつくりだしている。

そこに人々 のことを、ヒルズ族というのだそうだ。舗石が初秋の陽をはねかえす緩やかな斜面を、乳母車をおして下りてくる中年婦人のすがたもこの街の点景というところか。彼女が愛児とともに散策の足をはこぶ先は、「毛利庭園」である。それはビルの窓が覗きこむ擂鉢の底に、澄んだ水を溜めた「毛利池」とわずかな躑躅の群落を配した小公園だ。

入り口の表示板には「六本木ヒルズの緑のシンボルとして『空』と『緑』を感じられる日本庭園を作庭いたしました。この庭園では、古くからの地形を活かして池や流れを造るほか、クスノキ・サクラなど9本の既存の樹木を残して、春はサクラ、秋はモミジと季節の変化を楽しめる回遊式の庭園としました。平成十五年四月 六本木六丁目地区市街地再開発組合」とある。

毛利池の広さほどの空が真っ青な透明のドームとなって、頭上を覆っている。やはり庭園内に立つ別の表示板が、庭園のいわれを説明する。

「この地は、吉良庭討入りに加わった元赤穂藩士四十七人のうちの十人が預けられた長門長府藩毛利家麻布日ヶ窪上屋敷の一部である。中国地方の戦国大名毛利元就の孫に当たる秀元を初代とする毛利家は、現在の山口県下関市に藩庁を置いた外様大名(三万六千二百石)である」

この説明は誤りで、毛利本家は三十六万九千石、萩に本城をおき萩藩と称した。初代藩主は元就の曾孫にあたる秀就である。

現在の山口県下関市長府に城下をおいた長府藩(初代藩主秀元)は毛利の支藩であり、その長府藩の上屋敷が、麻布のここにあった。文化九年(一八一二)の『武鑑』では毛利甲斐守の公称石高を五万石余としてある。

今の麻布十番通り一帯は、徳川家康が江戸に城地を定めた当時からひらけた町だが、麻布台を下りた日ヶ窪あたりは、その名のとおり陽射しのわるい湿地帯のような場所だった。

「毛利庭園」の表示板には、さらに赤穂義士のことが書かれているので、ついでに読んでおこう。

元禄十五年(一七〇二)十二月十五日、藩主綱元は、家老田代要人を請取人として江戸詰諸藩士三百余人を、大目付仙石伯耆守邸(現在の港区虎ノ門二丁目八)に遣わした。

岡嶋八十右衛門常樹

吉田沢右衛門兼貞

武林唯七隆重

倉橋伝助武幸

間新六光風

村松喜兵衛秀直

杉野十平次次房

勝田新左衛門武尭

前原伊助宗房

小野寺幸右衛門秀富

の十人が日ヶ窪の江戸屋敷に収容された。

長府藩にお預けとなった赤穂義士十人が、この屋敷の裏門より送りこまれたとき、藩主毛利甲斐守綱元は在府中だった。ただちに屋敷内の長屋を急づくりの牢屋に仕立てて義士たちを入れ、あくまでも罪人として厳重に収檻した。

編年体の公式長府藩史『毛利家乗』では、受け入れ前半のいきさつを省略して、「日に饋ルニ盛饌ヲ以テス。必ず二膳アリ」と豪華な食事を供したとしているが、最初は粗末な一汁一菜しか与えなかった。

同じ義士を預かった大名でも熊本の細川綱利は、義士を仏子の鑑として優遇し、彼らを牢ではなく藩邸の座敷に収容した。毎日のご馳走ぜめに義士たちが音を上げたという。それにくらべて毛利氏のひどい仕打ちが江戸庶民の不評をかった。

「何等の冷酷、何等の無同情、武士の情も何もあったものではない。それで侠熱なる江戸っ子は非常に憤慨した」(福本誠『元禄快挙真相録』)

悪評に気づいて長府藩が義士のあつかいを変えたという話は、長府藩みずからが別に書き遺した資料に裏付けられている。

『毛利家乗』に収録された赤穂浪人預り一件の末尾に「遺臣等ヲ我ガ邸ニ看護スルヨリ幕裁ヲ受クルマデノ事実ハ別ニ赤穂浪人御預記ニ詳悉セリ」と、付記している。

その『赤穂浪人御預記』は下関市立長府図書館が所蔵する。

長州藩の義士にたいする冷遇を、後世におよんでも侮蔑をもって語る史家が少なくない。しかし長府藩みずからが、その状況を詳細な「事実」として記録したことの意味、そして二百数十年にわたる面従腹背の姿勢が、幕末の倒幕運動となって噴き出したことに思いを届かせる人はいないようだ。

関ヶ原で西軍の総大将となり、敗戦後、徳川に煮え湯をのまされたことへの屈折と卑屈な体質が、長く毛利氏の対幕姿勢に反映したのである。

幕府にむける怨嗟の視線が、幕府の警戒心を刺激した。ささいなことに因縁をつけられ、取りつぶしになるのではないかという密かな恐怖心を、毛利氏はいつもただよわせていた。

一、浪人に爪楊枝を与えてもよろしいか。

一、毛抜きを所望しているが与えてもよろしいか。

一、扇を所望しているが与えてもよろしいか。

一、発病したとき医者に診せてもよろしいか。

・・・・・・・・・・・・。

卑屈にそんなことを一々伺ったことが、細部にわたって『赤穂浪人御預記』に記録されている。やがて元禄十六年(一七〇三)二月四日「幕府、赤穂ノ遺臣ニ死ヲ賜フ。我ガ藩士進藤某等、コレガ死ヲ介ス」とあって、義士たちの自刃の実況を詳細に記録している。

岡嶋、吉田、武林といった順で切腹の座について。介錯人には五人の藩士が選ばれた。つまり一人で二人ずつを介錯した。

司馬遼太郎氏は、乃木希典のことを書いた『殉死』で、そのことを、「元禄のころの長府毛利家は士風がよほどおとろえていたのか、江戸詰めで剣を使える者がすくなく、浪士の切腹にあたってそれを介錯---首を落す---ことができる者はわずか五人しかいなかった」と云っている。

介錯人五人と聞いて、「士風がよほどおとろえていた」と即断し、地方の小藩の士風を嘲笑するのはどうであろうか。このとき伊予松山藩も預かった十人の義士を、五人の藩士が介錯している。では松山藩の士風もよほどおとろえていたことになるのか。

この日、長府藩邸で三番目に切腹の座についた武林唯七を介錯した藩士は、はじめての経験で動転したのか、手許が狂って一撃に失敗した。

「イマダ死セズ。顔色自若、即チ起キテ介者ヲ顧ミテ曰ク。徐ニセヨト。声イマダ了ラザルニ首隕ツ」

『毛利家乗』では、簡潔ではあるが隠さずこのように記録した。司馬さんの餌食にされても仕方がない場面だ。『殉死』は文中これを参考にして、悲惨な介錯の状況を次のように再現する。

榊は唯七の背後にまわり、唯七が腹に短刀を突き入れるや、あわただしく太刀をふりおろした。しかし太刀は唯七の頭蓋の下辺に激しくあたったのみで刃が跳ねかえり、落とせなかった。唯七は前に倒れ、しかし起きあがり、血みどろのまま姿勢を正し、「お静かに」と、榊に注意した。二度目の太刀で唯七の首が落ちた。

司馬さんは『殉死』の冒頭あたりで、「この書きものを、小説として書くのではなく」といっているが、長府藩士が介錯に失敗する情景は、みごとな想像力でできあがった手練の描写である。

----

Table of Contents

List of Maps

Introduction

Sumer

The Straits of Trade

Camels, Perfumes, and Prophets

The Baghdad-Canton Express

The Taste of Trade and the Captives of Trade

The Disease of Trade

Da Gama's Urge

A World Encompassed

The Coming of Corporations

Transplants

The Triumph and Tragedy of Free Trade

What Henry Bessemer Wrought

Collapse

The Battle of Seattle

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Illustration Credits

----

1

SUMER

The messages we receive from [the] remote past were neither intended for us, nor chosen by us, but are the casual relics of climate, geography, and human activity. They, too, remind us of the whimsical dimensions of our knowledge and the mysterious limits of our powers of discovery.---Daniel Boorstin

Sometime around 3000 BC, a tribe of herders attacked a small community of Sumerian farmers at harvest-time. From a safe distance, the attackers used slingshots, spears, and arrows that allowed them to achieve surprise. The farmers responded by closing in on their attackers with maces. The maces---a rounded stone attached to the end of a stout stick, designed to bash in the head of an opponent---was the first weapon specifically intended for use solely against fellow humans. (Animals had thick, angulated skulls that were rarely presented at an ideal angle to mace wielders.) Capable of crushing a man's fragile, round skull whether he was coming toward an attacker or running away, the mace proved especially effective.

There was nothing unusual about an attack at harvest time; the herders' goats and sheep were highly sensitive to disease and the vagaries of climate, and thus the nomadic tribe's survival required frequent raids to take grain from its more reliably provisioned crop-growing neighbors. In this particular battle, the herders wore a strange, shiny piece of headgear that seemed to partially protect them. Hard, direct mace blows, once lethal, now merely stunned, and many blows simply glanced off the headgear's smooth surface. This protective advantage radically changed the tactical balance of power between the two sides, enabling the herders to devastate the defending farmers.

After the attack, the surviving farmers examined the headgear from the few fallen herders. These "helmets" contained a sheet, one-eighth inch thick, of a wondrous new orange material fitted over a leather head cover. The farmers had never seen copper before, since none was produced in the flat alluvial land between the Tigris and Euphrates. Their nomadic rivals had in fact obtained the metal from traders who lived near its source hundreds of miles to the west, in the Sinai Desert. It was not long before Sumerian farmers obtained their own supplies, enabling them to devise more lethal spiked copper-headed maces, to which the herders responded with thicker helmets. Thus was born the arms race, which to this day relies on exotic metals obtained through commerce.

How did these farmers and herders obtain the copper for their helmets, and how was this trade conducted over the hundreds of miles between their farms and pastures and the copper mines? Paleoanthropologists believe that the best place to begin is about sixty to eighty thousand years ago, when the first genetically modern populations of humans in Africa began to develop more complex tools, pierce shells (presumably used in necklaces), and produce abstract images with pieces of red ochre. About fifty thousand years ago, small numbers of them probably migrated via Palestine into the Fertile Crescent and Europe. At some point prior to this trek, language developed, enabling more complex, uniquely "human" behavior: adroitly carved animal bone and antler tools, cave paintings and sculpture, and refined missile technologies, such as the atlatl, a specially crafted stick used to improve the range and accuracy of the spear. These increasingly sophisticated skills probably made possible yet another activity characteristic of modern humans: long-distance trade in the new weapons, tools, and knickknacks.

Historians, on the other hand, traditionally start with Herodotus's description, written around 430 BC, of the "silent trade" between the Carthaginians and "a race of men who live in a part of Libya beyond the Pillars of Hercules" (the Straits of Gibraltar), most likely today's west Africans:

On reaching this country, [the Carthaginians] unload their goods, arrange them tidily along the beach, and then, returning to their boats, raise a smoke. Seeing the smoke, the natives come down to the beach, place on the ground a certain quantity of gold in exchange for the goods, and go off again to a distance. The Carthaginians then come ashore and take a look at the gold; and if they think it represents a fair price for their wares, they collect it and go away; if, on the other hand, it seems too little, they go back aboard and wait, and the natives come and add to the gold until they are satisfied. There is perfect honesty on both sides; the Carthaginians never touch the gold until it equals in value what they have offered for sale, and the natives never touch the goods until the gold has been taken away.Alas, Herodotus's description of the decorum displayed on each side has an aroma of myth. Yet he probably got right the basic scenario right. On some unrecorded occasion deep in prehistory, a man, or several men, initiated early long-distance trade by setting out on the water in boats.

Hunger most likely got man into those primitive craft. Twenty thousand years ago, northern Europe resembled modern Lapland: a cold, uncultivated panorama dotted with fewer and smaller trees than are there today. Europe's first Homo sapiens, probably fresh from wiping out their Neanderthal rivals, subsisted primarily on large game, particularly reindeer. Even under ideal circumstances, hunting these fleet animals with spear or bow and arrow is an uncertain enterprise. The reindeer, however, had a weakness that mankind would mercilessly exploit: it swam poorly. While afloat, it is uniquely vulnerable, moving slowly with its antlers held high as it struggles to keep its nose above water. At some point, a Stone-Age genius, realized the enormous hunting advantage he would gain by being able to glide over the water's surface, and built the first boat. Once the easily overtaken and slaughtered prey had been hauled aboard, getting its carcass back to the tribal camp would have been far easier by boat than on land. It would not have taken long for mankind to apply this advantage to other goods.

Cave paintings and scattered maritime remains suggest that boats first appeared in northern Europe around fifteen thousand years ago. These early watercraft were made from animal skins sewed over rigid frames (most often antler horns) and were used for both hunting and transport, most commonly with a paddler in the rear and a weapon-bearing hunter or passenger in front. It is no accident that the reindeer-bone sewing needle appears simultaneously in the archeological record, since it is necessary for the manufacture of sewn-skin vessels. These first boats predate the more "primitive" dugout canoe, for the cold, steppe-like vista of northern Europe could not grow trees wide enough to accommodate a fur-clad hunter.

Only the most durable remnants, mainly stone tools, survive to provide hints about the nature of the earliest long-range commerce. One of the earliest commodities traded by boat must have been obsidian, a black volcanic rock (actually, a glass) that is a favorite of landscapers and gardeners around the world. Prehistoric man valued it not for its aesthetic properties, but rather because it was easily chipped into razor-sharp, if fragile, cutting tools and weapons. The historical value of obsidian lies in two facts: first, it is produced in only a handful of volcanic sites, and second, with the use of sophisticated atomic fingerprinting techniques, individual samples can be traced back to their original volcanic sources.

Obsidian flakes dating to over twelve thousand years ago found in the Francthi Cave in mainland Greece originated from the volcano on the island of Melos, one hundred miles offshore. These artifacts must have been carried in watercraft, yet there are no archaeological remains, literary fragments, or even oral traditions that inform us just how the obsidian got from Melos to the mainland. Were these flakes conveyed by merchants who traded them for local products, or were they simply retrieved by expeditions from the mainland communities who valued them?

Obsidian atomic fingerprints have been used to examine flows of the material through regions as disparate as the Fertile Crescent and the Yucatan. In the Middle East, the researcher Colin Renfrew matched up sites with sources dating from around 6000 BC. The amount of obsidian measured at each excavation site fell off dramatically with distance from its source, strongly suggesting that this was a result of trade. For example, all the stone blades found in the Mesopotamian sites came from one of two sites in Armenia. At a site 250 miles away from its volcanic source, about 50 percent of all of the chipped stone found was obsidian, whereas at a second site five hundred miles away from the source, only 2 percent of the chipped stone was obsidian.

These Stone-Age obsidian routes put into modern perspective the costs of prehistoric commerce. Transporting a load of obsidian between Armenia and Mesopotamia was the prehistoric equivalent of sending a family Christmas package from Boston to Washington, DC. But instead of paying a few dollars and handing the package over to a brown-clad clerk, this ancient shipment consumed two months (including the return trip) of a single trader's labor---very roughly, about $5,000 to $10,000 in current value.

With the advent of agriculture, this new maritime technology spread to settled farmers, who adopted the skin-and-frame design for river travel. A pattern of commerce commenced that would remain unchanged for thousands of years: traders from advanced farming communities would transport grain, farm animals, and basic manufactured items such as cloth and tools downriver to exchange for the wares, mainly animal skins, of the hunter-gatherers. Archeologists usually find the remains of these prehistoric markets on small, unforested river islands. This is no coincidence; these locations not only took advantage of boat transport but also minimized the odds of a successful ambush.

Axe and adze (chisel) blades, dating to about 5000 BC, survive as the main evidence of this Stone-Age waterborne commerce. Archaeologists have identified Balkan quarries as the source of the ax and blade material, fragments of which are found all the way from the mouth of the Danube at the Black Sea to the Baltic and North seas. These durable stone artifacts, found far from their identifiably unique sources, attest to a lively long-distance exchange in a rich multitude of goods.

Water transport is by its nature cheaper and more efficient than land carriage. A draft horse can carry about two hundred pounds on its back. With the help of a wagon and a good road, it can pull four thousand pounds. With the same energy expenditure, the same animal can draw as many as sixty thousand pounds along a canal towpath, a load that could be managed by small ancient sailing ships.

Herodotus also described similar sewn-skin vessels carrying wine "stored in casks made of the wood of the palm-tree." The ships were "round, like a shield," made of hide, and propelled by two Armenian merchants down the Euphrates to Babylon. Here, then, is the direct descendant of the earliest cargo ship used in maritime trade, a vessel relatively round in shape---and thus slow---so as to accommodate the most weight with the smallest crew and the minimal amount of building material. (By contrast, warships since ancient times have been narrow and fast, with smaller carrying capacities.)

The largest of these boats carried about fourteen tons and came equipped with several donkeys, so that at journey's end the wood frames could be scrapped and the precious skins packed up and carried back to Armenia on the beasts. Herodotus explains:

It is quite impossible to paddle the boats upstream because of the strength of the current, and that is why they are constructed of hide instead of wood. Back in Armenia with their donkeys, the men build another lot of boats to the same design.After returning to Armenia, the farmers would refit the skins over new frames and load the boats with fresh cargo, and the several-month journey to bartering centers would begin anew. No doubt, the Stone Age hunter-gatherers and farmers of northern Europe also paddled their goods downstream and packed their craft upstream in similar fashion.

Such were the likely beginnings of trade. Yet out of the desire to attack (or defend) territory was born one of the earliest and most enduring motifs of its history---the exchange of grain from advanced farming communities living in alluvial areas for metals, generally found in less fertile locales.

Around six thousand years ago, man figured out how to purify the abundant copper ore found just below the layers of the pure metal of the first virgin mines. Not long after, the Ergani mines in mountainous Anatolia (modern-day Asian Turkey) began shipping copper to the early settlements at Uruk (in what is now southern Iraq, about a hundred miles west of Basra). The Euphrates River connected Ergani and Uruk, and although the vessels of the day could easily float several tons of copper downstream to Uruk in a few weeks, the transport of hundreds of tons of grain to Anatolia, against the current, would have been much more problematic.

Later Mesopotamian civilizations took advantage of more favorably placed Persian Gulf mineral sources. The appearance of written records just before 3000 B.C. offers fleeting glimpses of a massive copper-grain trade that flourished along this route. The land of milk and honey from the ancient Sumerian creation myths was a place known as "Dilmun," celebrated for its wealth and probably located in modern-day Bahrain. Its prosperity, however, did not come from its relatively fertile soil, but rather from its strategic position as a trading post for copper produced in the land of Magan, in what is today Oman, just outside the Persian Gulf's entrance at the Strait of Hormuz.

Not far from modern-day Qal'at al-Bahrain, the archaeological excavation of ancient Dilmun's likely location has yielded a treasure trove of Bronze Age objects. The site covers only about fifty acres but contained a population of about 5,000, likely far more than could have been supported by the city's agricultural hinterland. Cuneiform texts record that small shipments, usually consisting of a few tons of barley, began to travel down the Gulf towards Dilmun and Magan around 2800 B.C. By the end of the millennium, these grain cargoes increased to as much as several hundred tons per shipload. At an astonishingly early point, history affords an ancient equivalent of Las Vegas-a large population living in relatively barren surroundings whose very survival depended upon large amounts of food imported from hundreds of miles away.

Dilmun's excavation provides a tantalizing, and oft times highly personal, window on what the Sumerian Persian Gulf grain-copper trade might have looked like. The town sat on an island and was supplied with a generous spring issuing what the ancients called "sweet," or fresh, water. By 2000 B.C., its city walls enclosed an area almost the size of the biggest Mesopotamian city, Ur. In its center sat a municipal square, one end of which opened on the sea gate; at the other end stood a building filled with seals and scales, almost certainly a customs house. Piled high around the square would have been huge baskets of barley and dates from the banks of the Tigris, while the more precious cargo-Mesopotamian cloth as well as ivory and ingots of copper bound for Ur-stood just outside the customs house, guarded by nervous sailors while their officers argued, bribed, and cajoled the officials inside.

If the year was 1800 B.C., these ingots would likely have been bound for the warehouses of Ea-nasir, the largest copper merchant in Ur, where archaeologists have discovered a large cache of clay tablets detailing this strategic trade. One tablet records a shipment of twenty tons of the metal, while another bears the complaint of a client, one Nanni: You said, "I will give good ingots to Gimil-Sin." That is what you said, but you have not done so; you offered bad ingots to my messenger saying "Take it or leave it." Who am I that you should treat me so? Are we not both gentlemen?"

The curiosity and drive of the first metal craftsmen who produced the copper in Ea-nasir's warehouses must have been remarkable. The process in which sulfur, oxygen, chlorine, or carbonate, depending on the type of ore, are removed from it to yield the pure metal-smelting-first saw the light of day in approximately 3500 B.C. The metallurgists of the Fertile Crescent soon began mixing their local copper with an exotic imported metal, tin. Not only was the new hammered copper/tin alloy as hard and durable as that of the previous copper/arsenic and copper/antimony alloys, but it melted at a much lower temperature than pure copper. Better yet, it did not bubble and was thus easily cast.

(Continues...)

----

----

Table Of Contents

Preface

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Contemporary Italian Philosophy: The Confrontation between Religious and Secular Thought

Maurizio Pagano

Part 1. Marking the Borders: Historical Legacies

1. The Desire for Eternal Life: The Platonic Roots of Western Political Science and Its Ethical and Theological Consequences

Carlo Sini

2. Philosophy, Poetry, and Dreaming

Sergio Givone

3. Christianity and Nihilism

Vincenzo Vitiello

4. Philosophy and Christian Theology Today: A Hermeneutic Circularity as Fact and Task

Giovanni Ferretti

5. Ontology of Actuality

Gianni Vattimo

Part 2. Crossing the Borders: Current Thematizations

6. Metaphysics of Thinking, Metaphysics of Being

Virgilio Melchiorre

7. The Truth of Existence and the Sacred (ethos anthropo daimon)

Mario Ruggenini

8. Transcendental without Illusion: Or, The Absence of the Third Person

Marco Maria Olivetti

9. Finitude and Responsibility: For an Ethics of the Finite in the Time of Risk

Salvatore Natoli

10. Praise of Modesty

Pier Aldo Rovatti

Part 3. Opening the Borders: The Appeal of the World

11. Logics of Delusion

Remo Bodei

12. Toward a Symbolic of Sexual Difference

Luisa Muraro

13. On Virtue

Emanuele Severino

14. Two Concepts of Utopia and the Idea of Global Justice

Salvatore Veca

15. The World and the West Today: The Problem of a Global Public Sphere

Giacomo Marramao

16. Names of Place: Border

Massimo Cacciari

Selected Bibliography

About the Editors

Contributors

Index

----

----

一 疑念

1

『……なぜだろう?』

博多行の新幹線〈こだま〉は、新下関駅で、後続の〈のぞみ〉の通過待ちをしていた。

沢野良介は、進行方向を背にして、向かい合わせに設えられた座席の窓側に座っていた。正面には三歳になる息子の良太が、隣に座る妻の佳枝の膝を枕にして眠っている。

駅弁の甘酸っぱい臭気が立ち籠める車内は、盆休みの帰省客で賑わっていた。所々で子供たちのはしゃぐ声が聞こえ、それを諫める大人たちの声が聞こえる。同乗の者と何と言うこともない世間話をしたり、実家の家族と携帯電話でこっそり到着時刻の確認をしたりする声が聞こえる。

良介は、自分が今いるそうした風景に、まだ硬い蕾のような感慨を覚え、目の焦点を曖昧にした。自分はこの場所に、ひとりの父親としている。――そう、父親なんだ。妻を伴い、子供を連れて両親の待つ実家に帰省しようとしている。いつの間にか、そうした年齢になってたんだ。……

丁度、そんなことを考えていた時だった。通路を歩く見知らぬ乗客が、通り過ぎ様にジロリと座席の人の顔を見て行くように、先ほどの言葉が脳裡を過ぎったのだった。

良介は、殆ど反射的に自分自身を顧みて、今度は改めてその言葉の方に目を遣り、見えなくなるまで、ずっとその後ろ姿を追っていた。確かに一瞬、目が合ったように感じた。しかし、その一瞥に、彼はまるで心当たりがなかった。そうした疑念がどこから来たのか分からなかったし、なぜ、自分を訪うたのかも分からなかった。しかし、一層奇妙に感じられたのは、それをただ、気のせいだとやり過ごすことが出来ずに、まるで何かを見咎められでもしたかのように、動揺してしまったことだった。

既に言葉は去っていたが、彼の中にはその一瞥の記憶が残った。そして、不安げにそれを覗き見ると、見られた自分が、そのまま身動きが取れなくなって、そこにまだじっとしているような気がした。

車内では、間延びした時間に倦んだ乗客たちの間に、彼方の新幹線の接近を探ろうとするような気配が立ち始めていた。五感には、まだ何も届けられてはいなかった。次の瞬間、突如として車体が傾くほどの衝撃が訪れると、車窓を一刷毛で猛然と白く塗り潰し、去り際にはまた律儀に車体の傾きを直して、あとの余韻も残さずに去っていった。何秒と数えるよりも、あっと言う間という慣用句がぴったりな感じだった。

発車のベルが長閑に鳴り響いて、ドアが閉ざされた。やがて、乗客の視界からホームの景色が少しずつ遅れ始めると、見る見る加速してそれが目まぐるしくなり、駅の全長は呆気なく辿り尽くされた。車窓は束の間晴れた後、関門トンネルに突入し、俄かに光を失って、代わりにそこに乗客たちを一斉に映し出した。

「あんなにたのしみにしてたのにねー。まってるあいだにつかれちゃったねー。」

佳枝は、良太の額をちょんとつつくと、半分は良介に聴かせるようにしてささやいた。

最寄駅の宇部新川からは、在来線を乗り継いで厚狭まで行き、そこからこだまで小倉まで一時間強という、旅程というほどのこともない移動のはずだった。それが、宇部駅で乗る予定の山陽本線で人身事故があって、復旧まで一時間半も待たされる羽目となった。自殺かどうかは分からなかったが、酷暑のホームで苛立つ乗客たちは、「死んでもいいけど、こんな時に飛び込まんでもなァ。」と愚痴を零し合っていた。

こだまとのぞみとの区別のつかない良太は、幼児用の雑誌の中にあったのぞみを描いた「しんかんせん」の絵を見て、昨晩はなかなか寝つかれないほどだったが、さすがにそれでくたびれ果てて、乗車するなり、佳枝の膝をねだって、ものの五分もする間にすっかり眠り込んでいた。

黒い綿のカーゴ・パンツ越しに、髪に籠もったその小さな頭の熱が、固い重みを伴って伝わってきた。佳枝は、日焼けして肘の谷にまた少し赤く兆したアトピー性皮膚炎を時折無意識に掻きながら、良太の顔を覗き込んでいた。

「もうついちゃうよー。おーい、たっくん。ちゃんと、あるけますかー?」

佳枝が顔を上げると、良介の目差しは、内へと滑り落ちそうになっていたところを、危うく引き戻されたというふうに、彼女の上に踏み留まった。そして、眸の奥で起こったそのほんの些細な出来事を悟らせないために、二三度素早く瞬きをすると、その隙に、さりげなく視線を良太の寝顔に逃がして、

「ギリギリになって起こせばいいよ。」

と小声で伝えた。

三歳になって、身長も丁度90センチと、さすがに大きくなったが、目を瞑る様子には、今もどこか、エコーで見る子宮の中の胎児のような、瞑想的なおとなしさがあった。起きている良太の相手をするのは楽しかったが、眠っている姿を眺めるのも好きだった。それは、父親になるまで想像もしなかった喜びだった。良介は、凡そ神秘的なもの、崇高なものへの関心を欠いていたが、寝ている良太の静けさには、一種、敬虔な気持ちになった。大人の寝顔は、こんなにも、その内側で何かが起こっている感じを抱かせないものだと彼は思っていた。――そう、何かが起こっている。それも、未来に向けて明るい何かが、着実に起こっている。そんな感じがした。

良太の小さく膨らんだ丸いほっぺたは、熟れ始めの白桃のように鮮やかなピンク色をしていた。そこにはまだ、どんな複雑な感情の陰影も刻まれた痕がなく、しかも、何かちょっとした力が加われば、それがいつまでも消えない傷を残してしまいそうだった。

良介は、今朝、鏡の前に立って見た自分の顔を思い出した。ユニット・バスの床には、昨夜の入浴後の冷えた水気がまだ残っていて、それがいつにも増して不快だった。通気口からは、分厚く強壮な蝉の啼き声が聞こえてくる。その響きは、今でも彼に、中学・高校時代の野球部の夏期休暇練習を思い出させた。

地元の私立大学を卒業した後、良介が就職したのは、宇部に本社のある化学薬品会社だった。最初の勤務地は大阪の研究所である。その後、二年間、千葉の工場の品質管理部に配属され、今年四月からは本社の営業部に異動していた。

良介は、自分が痩せたことに気がついた。あまりこまめに体重計に乗ったりはしない方で、四月の健康診断でも、体重は前年と変わらなかったので自覚しなかったが、電気シェイヴァーの山型のヘッドが、落ち窪んだ頬を捕らえそこなう感触から、彼は途中、何度となく、空いている左手で、肉の薄くなった顴骨の下の辺りを撫で摩った。

天井の蛍光灯の明かりは、却ってトンネルの中を夜のように錯覚させた。ドアの上の電光掲示板を、プロ野球の試合結果を伝える文字が、右から左へと流れてゆく。

やがて、小倉駅到着のアナウンスが流れると、それに合わせたかのようにトンネルが果て、車中は一瞬にして真夏の午後の光に満たされて、乗客たちはその明るさの中に吸い込まれた。

「さーて、おきてー、たっくん!」

佳枝は良太の肩を軽く叩きながら声をかけた。良太は、それを嫌がるふうに体を捩って、佳枝の股の間に逃げ込むように顔を埋めた。

「もー、どこにかおをつっこんでるの、アナタは? ほら、たっくん!」

佳枝は思わず吹き出しながら言った。良介は、靴を拾って良太に履かせてやると、

「ほら、たっくん。おきないと、おいていっちゃうぞー。」

と体を揺すり、自分はそのまま立ち上がって、佳枝の前を抜け、通路に出た。荷棚の旅行カバンは、前後の乗客の荷物に圧されて潰れかかっていた。腕を伸ばすと、彼は、二つのカバンと土産のはいった袋とを、佳枝たちに気をつけながら下ろして、空いているシートに並べた。

「はい、おきたー。おはよー、たっくん。おめめはさめましたか?」

『……なぜだろう?』

佳枝の声を聞きながら、荷物を纏める良介に、ふとまた、その言葉が耳打ちされた。しかし今度は、先ほどとは違って、半ば自分で意識しながら、それを呟いたようだった。

彼は、表情を曇らせて顔を上げた。そして、なぜか急に不安になって、降車客で混み合い始めた通路の先に目を遣った。出口が遠い気がした。二人を連れて、うまく出られるだろうか? あるいはと、後ろを振り返って、どちらが近いかを確かめようとした時、彼は、良太を傍らに抱いて座ったまま、じっとその様子を見ていた佳枝の目と、間違ってというふうな不用意さで出会してしまった。

「……ん?」

問われるよりも早く、彼はわざと口を固く結んで、両眉を持ち上げながら額に浅く皺を寄せた。

「ううん。……」

佳枝は咄嗟にそう応じて、続く言葉を微笑の中に曖昧に溶かした。そして、

「さぁ、たっくん、おりるよー。」

と良太の手を取り、促した。

良介は、前屈みになって、荷物の取っ手を両手に掴んだ。減速する車両に逆らって、上手くバランスを取ったつもりだったが、持ち上げた荷物が思いの外重く、小さくよろめくと、そのまま耐えきれずに、同じような家族連れの隣の乗客に、肩口からぶつかってしまった。

----

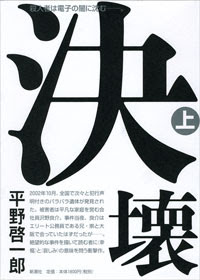

とにかく読ませる。芥川賞作家の力量が感じられる作品。

楊逸を読むより、こっちを読んだ方が面白いと思うんだけどなぁ。

----

List of figures

List of tables

Preface

Language and measures

Acknowledgements

Permissions

Part 1: 環境危機の「よく聞くお話」は本当か?(The Litany)

1 世の中、よくなってきているのだ(Things are getting better)

定番のお話(The Litany)

ものごとは改善している - が十分によくはない(Things are better - but not necessarily good)

誇張とよいマネジメント(Exaggeration and good management)

大事なことはトレンドである(Fundamentals: trends)

グローバルトレンドで判断する(Fundamentals: global trends)

長期トレンドと短期のリバウンド(Fundamentals: long-term trends)

なぜそれが重要なのか?(Fundamentals: how is it important?)

人間のニーズこそ核心となる(Fundamentals: people)

ワールドウォッチ研究所の主張(Reality: Worldwatch Institute)

地球環境の現実と神話(Reality versus myths)

WWF(世界自然保護基金)の宣言(Reality: World Wide Fund for Nature

グリーンピースの戦略(Reality: Greenpeace)

まちがったダメな統計と経済学(Reality: wrong bad statistics and economics)

水は不足しているか(Reality: water problems)

ピメンテルと世界の健康 その一(Reality: Pimentel and global health I)

ピメンテルと世界の健康 その二(Reality: Pimentel and global health II)

レトリックとダメな予想(Reality versus rhetoric and poor predictions)

現実はどうか?(Reality)

現実と道徳(Reality and morality)

2 なぜ悪いニュースばかり流されるのか?(Why do we hear so much bad news?)

研究と偏り(Research)

ファイル棚とデータマッサージ(The file drawer and data massage)

団体の利害関係(Organizations)

メディアの影響(The media)

歪んだ現実:散発的だけれど予想がつく(Lopsided reality: sporadic but predictable)

歪んだ現実:悪いニュースがニュース(Lopsided reality: bad news)

歪んだ現実:対立と罪悪感のパターン(Lopsided reality: conflict and guilt)

その帰結(The consequences)

Part II: 人間の福祉はどんな状態か?(Human welfare)

3 人類の福祉を計る(Measuring human welfare)

地上には何人いるのか?(How many people on earth?)

人口構成の変化(The changing demographics)

人口過剰?(Overpopulation)

4 期待寿命と健康(Life expectancy and health)

期待寿命(Life expectancy)

発展途上国の期待寿命(Life expectancy in the developing world)

乳児死亡率の低下(Infant mortality)

制圧された病気たち(Illness)

結論(Conclusion)

5 食糧と飢え(Food and hunger)

マルサスと「永遠に続く飢餓」説(Malthus and everlasting hunger)

かつてないほど食糧は増えている(More food than ever)

かつてないほど値段は下がっている(Lower prices than ever)

緑の革命(The Green Revolution)

相対的な改善?絶対的な改善?(Relative or absolute improvement?)

アフリカの実態(Regional distribution: Africa)

中国の実態(Regional distribution: China)

結論(Conclusion)

インフレ調整済みGDPは豊かさの指標として適当か?(Is inflation-adjusted GDP a reasonable measure of wealth?)

6 かつてない繁栄(Prosperity)

貧困と分配(Poverty and distribution)

貧富の差は拡大しているか?(Ever greater inequality?)

成長危機の真の原因(Poorer still?)

増えた消費財(More cunsumer goods)

教育水準の向上(More education)

増えた余暇(More leisure time)

治安の向上(More safety and security)

少なくなった災害と事故(Fewer catastrophes and accidents)

7 Conclusion to Part II: かつてない人類の繁栄(unprecedented human prosperity)

Part III: 人類の繁栄は維持できるのか?(Can human prosperity continue?)

8 ぼくたちは未来を食いつぶして、現在の繁栄を維持しているのか?(Are we living on borrowed time?)

資源 - 福祉の基盤(Resources - the foundation for welfare)

9 食べ物は足りているか?(Will we have enough food?)

少なくとも一人あたり穀物は減少しているが(At least grain per capita is declining)

生産性低下は心配すべきか?(Declining productivity)

収量の限界?(Limits to yields?)

バイオマス(緑の物質)(Biomass)

ふつうの農民はどうか?(What about ordinary peasants?)

まだ収量の高成長が必要なのか?(Do we need the high growth?)

穀物備蓄が減っている!(Grain stocks are dropping!)

中国はどうか?(What about China?)

土壌流出は心配か?(Should we worry about erosion?)

魚はどうか?(What about fish?)

結論(Conclusion)

10 森林はなくなりかけているのか?(Forests - are we losing them?)

森林と歴史(Forests and history)

森林破壊の一般的な見解(Deforestation: general view)

森林はどれだけ破壊されたか?(Deforestation: how much?)

どれだけの森林があればいいのか?(How much forest?)

結論(Conclusion)

11 エネルギーは枯渇するか?(Energy)

エネルギー上に築かれた文明(We are a civilization built on energy)

このままやっていけるだけのエネルギーはあるか?(Do we have enough energy to go on?)

石油危機とは何だったのか?(The oil crisis)

石油はどれだけ残っているのか?(How much oil left?)

楽観論者と悲観論者(Optimists and pessimists arguing)

使える石油はかつてなく多い(Ever more oil available)

その他の化石エネルギー源(Other fossil energy sources)

原子力エネルギー(Nuclear energy)

再生可能エネルギー(Renewable energy)

太陽光エネルギー(Solar energy)

風力エネルギー(Wind energy)

エネルギー貯蔵(Storage and mobile consumption)

結論(Conclusion)

12 エネルギー以外の資源(Non-energy resources)

悲観論者は資源が枯渇するほうに賭け-そして負けた(The pessimists bet on resources running out and lost)

下落する価格(Falling prices)

セメント(Cement)

アルミニウム(Aluminum)

鉄(Iron)

銅(Copper)

金と銀(Gold and silver)

窒素、リン、カリウム(Nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium)

亜鉛(Zinc)

その他の資源(Other resources)

なぜ資源が増えたりするのか?(Why do we have ever more resources?)

結論(Conclusion)

13 水は十分にある(Water)

水は世界にどれだけあるのか?(How much water in the world?)

三つの中心的な問題(The three central problems)

水が足りない?(Not enough water?)

将来はもっと悪化する?(Will it get worse in the future?)

水をめぐる紛争が激しくなる?(Will we see increased conflict?)

結論(Conclusion)

14 Conclusion to Part III: 繁栄は続く(continued prosperity)

Part IV: 公害は人間の繁栄をダメにするか?(Pollution: does it undercut human prosperity?)

15 大気汚染(Air pollution)

昔の大気汚染(Air pollution in times past)

何が危険なのか?(What is dangerous?)

微粒子(粒子状物質)(Particles)

鉛(Lead)

二酸化硫黄(SO2)

オゾン(Ozone)

窒素酸化物(NOx)

一酸化炭素(CO)

発展途上国の所得と汚染の関係(And the developing world? Both growth and environment)

結論(Conclusion)

16 酸性雨で森は死んでいるか?(Acid rain and forest death)

17 屋内の空気汚染のほうが深刻(Indoor air pollution)

発展途上国の屋内の空気汚染(Indoor air pollution in the developing world)

先進国における屋内の空気汚染(Indoor air pollution in the developed world)

18 アレルギーとぜん息(Allergies and asthma)

19 水質汚染(Water pollution)

海の石油汚染(Oil pollution in the oceans)

ペルシャ湾の石油(Oil in the Gulf)

エクソン・バルディーズは相変わらず大惨事なのか?(Exxon Valdez: still a catastrophe?)

沿岸の海水汚染(Pollution in coastal waters)

沿岸水の窒息(Suffocation in coastal waters)

肥料による健康への影響(Health effects from fertilizer)

河川の汚染(Pollution in rivers)

20 廃棄物の捨て場はないのか?(Waste: running out of space?)

21 Conclusion to Part IV: 公害の負担は減りつつある(the pollution burden has diminished)

Part V: 明日の問題(Tomorrow's problems)

22 化学物質がこわい(Our chemical fears)

ガンの死亡率(Cancer: death)

ガンの発生率(Cancer: incidence)

「八人に一人」と他の生涯リスク(1-in-8 and other lifetime risk analysis)

農薬がこわい(The fear of pesticides)

リスク分析によって閾値を定める(Establishing thresholds through risk analysis)

農薬とガン(Pesticides and cancer)

動物実験におけるガン(Cancer in animal experiments)

天然農薬と合成農薬(Natural and synthetic pesticides)

合成卵胞ホルモン(環境ホルモン)(Synthetic estrogens)

合成卵胞ホルモンで精子は劣化したか?(Synthetic estrogens: a fall in sperm quality)

有機農法の農民たち(Organic farmers)

合成卵胞ホルモンの「カクテル効果」(Synthetic estrogens: the "cocktail" effect)

合成卵胞ホルモンと乳ガン(Synthetic estrogens: breast cancer)

合成卵胞ホルモンは本当に心配すべきか?(Synthetic estrogens: should we worry?)

Conclusion: 農薬を使うべきか?(should we use pesticides?)

23 生物多様性の問題(Biodiversity)

生物の種は全部でどのくらいあるのか?(How many species are there?)

生物多様性は本当に大事なのか?(Is biodiversity important?)

どれくらいの種が絶滅しているのか?(How many go extinct?)

四万種という主張(The claim of 40,000 species)

モデルによる裏付け(A model backup)

ぼくたちは何を失うのか?(What do we lose?)

モデルと現実(Models and reality)

生物学者の反応(The biologists' reaction)

データをチェックしよう(Check the data)

義務を放棄する生物学者(The biologists' response)

Conclusion: 絶滅を派手に誇張したらどうなるのか?(what are the consequences of seriously overstating the extinctions?)

24 地球温暖化(Global warming)

温室効果の基礎(The basic greenhouse effect)

長期の気候の動き(The long-term development of the climate)

一八五六-二一〇〇年の気候(The climate, 1856-2100)

二酸化炭素は気温にどれくらい影響するのか?(How much does CO2 affect the temperature?)

微粒子の冷却効果(How much does CO2 affect the temperature? Particles)

水蒸気フィードバック(How much does CO2 affect the temperature? Water vapor)

雲のフィードバック(How much does CO2 affect the temperature? Clouds)

オゾンホール(The ozone hole)

他に原因はないのか?(Are there other causes?)

シナリオは現実的なのか?(Are the scenarios realistic?)

四〇の新シナリオ(Are the scenarios realistic? The 40 new scenarios)

農業への影響(Consequences: agriculture)

海面上昇(Consequences: sea level rise)

人類の健康(Consequences: human health)

異常気象(Consequences: extreme weather)

現在と未来の気候(Consequences: present and future weather)

温暖化のコスト(The cost of warming)

二酸化炭素削減のコスト(The cost of cutting CO2)

では、どうすればいいのか?(Then what should we do?)

二重の賭け:環境を改善しておまけに儲ける?(The double dividend: improve the environment and make money?)

反対論(1)二酸化炭素を削減して儲けよう(Objections: cut CO2 and make money)

反対論(2)未来のお値段(Objections: the price of the future)

反対論(3)大災厄がこわい(Objections: the fear of catastrophe)

まとめ(Summing up)

どんな未来社会を好むのか(More than meets the eye)

Conclusion: 怪談としっかりした政策(scares and sound policy)

Part VI: 世界の本当の状態(The Real State of the World)

25 窮地なのか、進歩なのか?(Predicament or progress?)

定番話という壮大な寓話(The Great Fable of the Litany)

世界の本当の状態(The Real State of the World)

それなのにもっと心配するぼくたち(Yet we worry ever more)

優先順位の設定とリスク(Setting priorities and risks)

リスクの重みづけ(Weighing risks)

定番話のコスト(The costs of the Litany)

遺伝子組み換え食品:定番話の総集編(Genetically modified foods - the encapsulation of the Litany)

「慎重なる回避」原理(予防原則)の問題点(Caution when invoking the principle)

繁栄は続くのだ(Continued progress)

注(Notes)

(Bibliography)

(Index)

What kind of state is the world really in?

Optimists proclaim the end of history with the best of all possible worlds at hand, whereas pessimists see a world in decline and find doomsday lurking around the corner. Getting the state of the world right is important because it defines humanity's problems and shows us where our actions are most needed. At the same time, it is also a scorecard for our ablilities, and is this a world we want to leave for our children?

This book is the work of a skeptical environmentalist. Environmentalist, because I - like most others - care for our Earth and care for the future health and wellbeing of its succeeding generations. Skeptical, because I care enough to want us not just to act on the myths of both optimists and pessimists. Instead, we need to use the best available information to join others in the common goal of making a better tomorrow.

Thus, this book attempts to measure the real state of the world. Of course, it is not possible to write a book (or even lots and lots of books for that matter) which measures the entire state of the world. Not is this my intention. Instead, I wish to gauge the most important characteristics of our state of the world - the fundamentals. And these should be assessed not on myths but on the best available facts. Hence, the real state of the world.

The Litany

The subtitle of my book is a play on the world's best-known book on the environment. The State of the World. This has been published every year since 1984 by the Worldwatch Institute and its leader Lester Brown, and it has sold more than a million copies. The series attempts to identify the world's most significant challenges professionally and veraciously. Unfortunately, as we shall see, it is frequently unable to live up to its objectives. In many ways, though, The State of the World is one of the best-researched and academically most ambitious environmental policy publications, and therefore it is also an essential participant in the discussion on the State of the World.

On a higher level this book plays to our general understanding of the environment: the Litany of our ever deteriorating environment. This is the view of the environment that is shaped by the images and messages that confront us each day on television, in the newspapers, in political statements and in conversations at work and at the kitchen table. This is why Time magazine can start off an article in 2000, stating as entirely obvious how "everyone knows the planet is in bad shape."

Even children are told the Litany, here from Oxford University Press Young Oxford Books: "The balance of nature is delicate but essential for life. Humans have upset that balance, stripping the land of its green cover, choking the air, and poisoning the seas.

Equally, another Time article tells us how "for more than 40 years, earth has been sending out distress signals" but while "we've staged a procession of Earth Days . . . the decline of Earth's ecosystems has continued unabated. The April 2001 Global Environment Supplement from New Scientist talks about the impending "catastrophe" and how we risk consigning "humanity to the dustbin of evolutionary history." Our impact is summarized with the headline "Self-destruct";

----

"Life expectancy"を「平均寿命」と訳さず、敢えて「期待寿命」と訳す意味は何だろう?

日本語版への序文----

はじめに(Foreword)

第一章 リベラリズムの死(The Death of Liberalism)

第二章 ウォール街の新たな宗教(Wall Street Finds Religion)

第三章 バブルの国への道(Bubble Land: Practice Runs)

第四章 資金の壁(A Wall of Money)

第五章 ドルの津波(A Tsunami of Dollars)

第六章 大規模な清算(The Great Unwinding)

第七章 勝者と敗者(Winners and Losers)

第八章 均衡の回復(Recovering Balance)

原 註(Notes)

解 説

For connoisseurs of misery, the ten years from 1973 through 1982 are feast of low points.

The rate of economic growth was one of the worst for any comparable period since the end of World War II. The country endured one of the worst periods of inflation in American history, and foreign investors fled the dollar as if it were the Mexican peso.

Japanese companies humiliated American standard-bearers in one flagship industry after another. Layoffs and short shifts spread through heavy industry. America's once-humming industrial heartland transmuted into the Rust Belt.

The OPEC nations increased oil prices tenfold and strongarmed their way into ownership interests in Big Oil's production arms.

There were war protests and campus battles. Cities were awash in crime and disorder. New York City went to the edge of bankruptcy. A president was forced from office, and his vice president resigned over charges of bribery and corruption.

Helicopters evacuated Americans from the embassy rooftop in Saigon, fleeing a lost war. The Soviet Union visibly stepped up the missile race and sent 100,000 troops into Afghanistan. President Jimmy Carter spent the last months of his presidency negotiating ransom payments for fifty-two American hostages held by Iranian radicals.

Economists even came up with a measure of how awful it felt. In 1980, the Misery Index, the sum of the inflation rate and the unemployment rate, was the highest ever. An ugly new word, "stagflation," entered the political vocabulary.

Events so pervasive and so consequential are usually overly determined. There is no one cause, but lots of causes. The 1970s disasters had at least three primary roots---the loss of business vision, demographic shifts, and gross economic mismanagement.

Business Embraces Incompetence

Consider a listing of the top American companies from about 1910 or so:It would include U.S. Steel and Bethlehem Steel; Standard Oil and Gulf; Swift, Armour, and General Foods; AT&T, General Electric, and Westinghouse; Anaconda Copper and Alcoa; Dupont and American Tobacco. Then look at a listing from the late 1970s. Except for companies from new industries, like General Motors and RCA, it's much the same. Despite all the vicissitudes of mergers, name changes, and antitrust, the top companies in 1910 mostly held their positions for the next seventy years.

The winning companies of the early 1900s had emerged from the most savagely Darwinian industrial maelstrom in history. Rockefeller, Carnegie, and their ilk clawed to the top through ruthless efficiency and lethal execution. The best German or British chemical and steel companies could beat the Americans in this or that niche, but across the board, the United States possessed the most formidable array of industrial power ever seen.

And then Americans slacked off.

Almost as soon as U.S. Steel was born from a string of mergers in 1901, its chief, Elbert Gary, started working out market-sharing and price-maintenance agreements with his competition. U.S. Steel was born controlling more than half the market; Gary argued that if his fellow steel moguls just adopted U.S. Steel's high price structure, they would each maintain their market shares and all could flourish together. After the Standard breakup in 1911, the oil industry fell into a similar pattern, and eventually so did newer industries, like automobiles and televisions. A steel company chief once explained the logic of price maintenance to a Senate antitrust committee: "If we were to lower our prices, then it would be met by our competitors, and that would drop their profit, so we would still be right back to the same price relatively.

War preserved and extended Americans' lazy hegemonies. Companies could wax fat on wartime weapons orders and postwar reconstruction, and at the same time help destroy their overseas competitors. A 1950s steel sales executive bragged, "Our salesmen don't sell steel; they allocate it." But by defanging competition, Gary's system of "administered pricing" froze technology. The locus of innovation in steel-making shifted to Europe and Japan.

Big Labor was inducted into the system in the 1950s, with the General Motors formula for labor settlements. The industry price-setter usually took the land in union negotiations. Contracts would normally cover three years and would include wage awards in line with forecasted productivity increases. Later, as inflation ticked up, contracts includes both the expected productivity increase plus annual adjustments for inflation accelerated at the same time, the companies were left with a cost problem they could not wish away.

Even contemporaries understood that the 1950s and early 1960s were something of a golden age. Big-company pay-settlement standards percolated throughout the smaller companies that supplied them, and most companies were adding pension and health benefits. For a large slice of the population, the American dream of a house with a lawn and a decent school for the kids came true. John Kenneth Galbraith's The Affluent Society (1958) announced that the problem of production had been solved, that consumer wants were on the verge of being sated, and that it was time to focus on "expelling pain, tension, sorrow, and the ubiquitous curse of ignorance."

Labor schools for union activists flourished in the 1950s and 1960s. Most of them were run by Catholics, many at Jesuit colleges. (The big industrial unions were often two-thirds Catholic.) The schools taught bargaining and organization techniques, labor law, and labor economics, while extolling the "solidarist" power-sharing arrangements characteristic of Catholic Europe. Businessmen often attended the courses. Union leaders and executives began to regard themselves as industrial statesmen.

At the business schools, the reign of the big companies was taken as part of the natural order. The hot topics of the 1950s and 1960s were organization and finance, essentially rearranging furniture within the stable multi-unit enterprises of modern "managerial capitalism." There was a 1960s merger movement, but it had an academic, chalk-dust smell. The idea was that if companies assembled diverse portfolios of businesses, they could smooth out their earnings cycles. Absurdly, Exxon went into office equipment; Mobil bought a circus and a department store chain.

昨日、「黒船レディと銀星楽団」のライブに行ってきた。

http://kurofunelady.net/

場所は吉祥寺STAR PINE'S CAFE。

http://www.mandala.gr.jp/spc.html

そもそもの話、

黒船レディ(vo)さんは、親戚とは言い難い、従甥の従姉妹(やや遠い関係)。

当然つい最近まで面識はなかった。

で先月、従甥の結婚式があり

披露宴で「黒船レディと銀星楽団」がパフォーマンスを披露し、

それを見て僕は初めてその存在を知り、

そして「今度ライブやります」と聞いて、

直近のライブが昨日だったので足を運んだ。

ライブは10分遅れでスタート。

会場は、おそらく9割は埋まっている(ように見えた)。

音楽的には、懐かしくJazzyな感じ。

ボーカルが特徴的でノビがありかつキュートな美声を聞かせてくれる。

伴奏も総じてレベルが高く聞いていて心地よい。

いつもは4人で演奏しているところ、

今日のライブは、フルアルバムのリリース・パーティということで

総勢12名+DJ6名という「ものすごい!」大所帯。

そのおかげもあって、結婚式のパフォーマンスで聞いたときより

はるかに迫力があり、抜群のノリの良さがあった。

途中、新曲の披露があり、

店に頼んで作ってもらったスペシャル・カクテルの紹介があり、

アンコールの2曲目を終える頃には、

黒船レディさんも涙ぐんでいた(ように見えた)。

正直なところ、1st、2nd、encore併せて2時間ぐらいの時間、

楽しい時間を過ごさせてもらった。

セットリスト

<1st>

1.Doodling' Song

2.夜来香

3.鳥にないたい

4.そよ風の誘惑~ Have You Never Been Mellow? ~

5.Collage

6.Make up! Swing

7.亡き王女のためのパヴァーヌ~ Pavane Pour Une Infante Defunte ~

8.古本屋のワルツ

9.Bandoneon

10.Amapola

<2nd>

1.C'est Magnifique

2.ダンシングシスターズ~ I’m In The Mood For Dancing ~

3.Holiday

4.忘れもの~ Do You Know What It Means To Miss New Orleans? ~

5.金色のそら

6.雨~Rain

7.いちばんほしいもの

8.Gumbo!

1.Wrap Your Troubles In Dreams

2.(失念)

目次----

第一章 東京裁判に呪縛されていた「司馬史観」の軌跡

「両刃の剣」であった「司馬史観」

そもそも戦争を裁く国際的な法源はなかった

東京裁判はどれほど茶番だったのか

「戦前は暗黒時代」と日本人に刷り込む

司馬氏のノモンハン事件の解釈が問題点

ノモンハン事件の勝敗が変わった

権威を否定して行き着くところは

司馬氏も逃れられなかった「ソ連神話」

第二章 司馬遼太郎氏の作品にみる「司馬史観」の誕生と形成

読み返して改めて司馬氏の作品に感動

司馬氏の歴史小説の三つの手法

幕末のストーリーに昭和史を挟み込む

結果を前提とした歴史認識の傾向がある

なぜ『坂の上の雲』のあとに『翔ぶが如く』を

司馬氏が繰り返し述べる呪詛のようなつぶやき

立国の基本、日本の美風が失われると

「合理主義的歴史観」では滅びの美学はわからない

私学校党に昭和の軍閥を投影する

善玉と悪玉のフィクションに過ぎない

昭和史の偏見や呪縛から解放されるために

好き嫌いの両極端にふれる人物描写

思い込みの強さがソ連神話にもつながった

第三章 東京裁判が今もなお醸成する「閉ざされた言語空間」

私自身が経験した、ある異常な事件

従軍慰安婦問題の問題点から始めよう

声高に言い立てる人が真実を語るとは限らない

問題の核心が反日運動などにすりかえられている

詐欺とペテンが通ってしまう日本社会の空気

論理のすりかえで延命を図る風潮

「君は権力的だ」という言葉の魔術

「思考のトリックと論理の錯覚」に陥るな

自主規制こそ一番悪しき言論のファシズム

日本を震源とする亡霊が外交カードに

お互いに不幸になる意識のギャップ

まずは日本人のモラルやエートス

近代化と経済発展のエートスとは

第四章 東京裁判史観とは正反対。戦前のアジア情勢と国際世論

白人の視点から見た戦前の日本像

「日本軍の足跡をたどって・・・・・・日本軍部隊がシナ大陸で与えた損害は、敗走するシナ軍によるものより僅か」

「日本、戦争の中でその東洋的平静さを堅持」

「私の見た満州国、この国の驚くべき発展」

「日本の立場」

日本の立場を理解させる努力を

第5章 司馬遼太郎氏の作品に映し出される「戦後精神」

自虐史観や東京裁判史観には批判的でも「司馬史観」には甘い

司馬氏がノモンハン事件を小説にしたら悪役は服部・辻の両参謀

『スターリングラード』という映画を見るとノモンハンでのソ連軍がわかる

平和主義が戦争を起こしたという歴史の皮肉な教訓

小説のフィクションが史実だと勘違いされる恐ろしさ

締め括りにかえて

今の日本のアノミーをもたらしたものが何であったのか、理解していただけただろうか

後記として

著者の福井雄三は1953年鳥取県倉吉市生まれ。

東京大学法学部を卒業後、企業勤務を経て、1992年より大阪青山短期大学助教授。

専攻は国際政治学、日本近現代史。

この本はパル氏の次の言葉から始まる。

----

時が熱狂と偏見を和らげたあかつきには、

理性が虚偽からその仮面を剥ぎ取ったあかつきには、

その時こそ、

正義の女神はその秤を平衡に保ちながら、

過去の賞罰の多くに、そのところを変えることを

要求するであろう

----

第一章

----

司馬史観においては、旅順攻防戦とノモンハン事件は好対照をなして屹立する両巨峰である。司馬氏の思考回路の中でこの両事例は、決して別個の事件ではない。車の両輪の如くにからまり合い、相互に関連し合っている、表裏一体のテーマとしてとらえられているはずだ。

----

第二章

----

『伊地知、日本は旅順だけで戦っているのではない。そんなことがわからんのか』

『閣下の責任を問うているのです』

『お前は女か』

----

砲弾不足を訴える伊地知と児玉の会話(上)を引用した後で、『坂の上の雲』のいわば悪玉コンビとでも呼べそうな、乃木と伊地知は、司馬作品に頻出するひとつのパターンだと福井は指摘する。

----

『坂の上の雲』の乃木希典と伊地知幸介が、『翔ぶが如く』の西郷隆盛と桐野利秋のイメージに重なり合うことに、読者諸氏は気づかれたであろう。この「乃木的」なものと「伊地知的」なものに象徴される人物像のコンビは、司馬氏のあらゆる作品に姿を変え形を変えて現れ続ける。司馬氏の構想ではそれが最終的に、ノモンハン事件の服部卓四郎と辻政信のコンビとして描かれるはずであった。

----

第三章では慰安婦に関する思考の前提事項が述べられる。

----

第一に、慰安婦は当時の職業の一つであった。

第二に、慰安婦は当時合法であって違法ではない。

第三に、戦地に、慰安婦という娼婦はいたが、「従軍」慰安婦という娼婦はいなかった。

第四に、強制連行は無かった。悲しい話だが、希望者がたくさんいる娼婦を強制連行する理由がないではないか。簡単にいうと、戦地で日本の兵隊を相手に商売した娼婦や慰安婦はいたが、従軍した娼婦や慰安婦などいない。まして日本軍が何の必要があって、娼婦や慰安婦を強制連行しなければならないのか。だから、当然ながら、強制連行の事実はまったくない。

----

もし、慰安婦強制連行の廉で「日本を告発するのであれば、提訴する側に立証責任があ」り、「命令したのはどこの役所のどの部署」なのか、「担当した責任者の名は誰」なのか、「命令を伝える公文書はどこに保管されているの」か、「強制連行したという輸送手段、日付、人数」を提示しなければならない。

以下、この本で紹介されている本。

小田洋太郎『ノモンハン事件の真相と戦果』(有朋書院)

「この書は、ノモンハン事件の戦闘で日本軍がソ連軍を撃破した記録が満載・網羅されている、近年屈指の好著である。当時の膨大な史料や記録、あるいは戦闘に参加した兵士の手記などを、戦闘経過の日付に沿いながら丹念に集め、各日付ごとの記録として、時系列的に集大成された小田氏の努力には、頭が下がる思いである。この著書は今後、ノモンハン事件を再検証する上で、不可欠の史料となるであろう」

別宮暖朗『旅順攻防戦』(並木書房)

「私はこの本を一読して、その正確な軍事知識と歴史認識と緻密な論理構成に驚嘆した。(中略)旅順攻防戦に関して私が到達したのと同様の見解を抱いていた人が、他にもいたことを知って、大いに勇気づけられたものである。

別宮氏は第一次世界大戦の戦史研究に造詣が深く、その軍事知識は微にいり細にわたって詳細を究めている。軍学者兵頭二十八氏との対談をふまえ、膨大にしてかつ詳細な軍事知識と、正確な歴史認識に裏打ちされた氏の日露戦争研究は、今後ともこの分野を研究する者にとって最良の指針となるであろう」(第二章)

シェンキビッチ(Henryk Adam Aleksander Pius Sienkiewicz)『クオ・バディス(Quo Vadis)』

この本は滅びの美学を表現している文学作品の一つとして紹介されている。

「ローマ皇帝ネロの時代のキリスト教迫害をテーマにした、壮大なストーリーである」

「(ペトロニウスは)政敵チゲリヌスとの権力闘争に敗れた後、最後は愛する女奴隷のエウニケとともに従容として自殺して果てるのであるが、このペトロニウスは実に魅力的な人物である」(第二章)

カール・カワカミ(Kiyoshi Karl Kawakami)『シナ大陸の真相(Japan in China, Her Motives and Aims)』(展転社)

「あの当時のあの状況の中で、欧米の側から発せられた本格的な日本弁護論という点において、この本は後世の歴史家による後知恵や粉飾とは無縁の、まさにリアルタイムの歴史的価値を持つ本である」(第五章)

河上清(カール・カワカミ)は、米沢中学校(現山形県立米沢興譲館高等学校)卒業後、万朝報記者となり社会主義とキリスト教に関心を抱き、足尾銅山鉱毒事件などの追及を行った。1901年社会民主党の結成に加わるが、同党が禁止されると、身の危険を感じて渡米。大学で学びながらジャーナリストとしての活動も再開。キヨシ・カール・カワカミ(K.K.カワカミ)の筆名を用いる。(Wikipedia)

クリストファー・ソーン(Christopher G. Thorne)『米英にとっての太平洋戦争(Allies of a Kind: the United States, Britain, and the War against Japan, 1941-1945)』(草思社)

「戦勝国イギリスの学者でありながら、勝者と敗者の立場を越えて、太平洋戦争という歴史的事象をリアルポリティーク、バランスパワーの視点から、冷徹に分析した、この本の著者の知的強靭さには脱帽せざるを得ない」(第五章)

----

This book tells the story of two successive transformations of the Western legal tradition under the impact of two Great Revolutions---the sixteenth-century German Revolution, of which the Lutheran Reformation was a critical part, and the seventeenth-century English Revolution, of which the Calvinist Reformation was a critical part. It was, of course, not just the legal tradition that was affected by these revolutions; also involved were new forms of nationhood, new forms of government, new concepts of truth. These were two total political and social upheavals, reflecting two new belief systems, whose repercussions were felt throughout Europe.

One cannot properly tell the story of what happened to the Western legal tradition in these two successive periods of history without also sketching its background in the revolutionary changes as a whole: what happened in Germany---and in Europe---after October 31, 1517, when Martin Luther posted his Ninety-five Theses on the door of his prince's church in Wittenberg, declaring, in effect, the abolition of the Roman Catholic priesthood, and rulers of German principalities raised armies to defend the Lutheran cause against the forces of the German emperor and the papacy; and what happened in England, and in Europe, after November 1640, when, following eleven years of personal rule by Charles I, a Puritan-dominated Parliament, elected by the English landed gentry, voted to establish the Presbyterian Church in Scotland, causing Charles to bring four hundred troops into the House of Commons for the purpose of arresting leading members, after which Parliament raised an army of its own to bring down royal supremacy. The main focus of the book, however, is not on the course of the two revolutions but rather on what happened eventually, in their wake, to the systems of law in the two countries, viewed in the context of the larger legal tradition of which the two national legal systems were a part.

An earlier volume told the story of the formation of the Western legal tradition. Under the impact of the Papal Revolution of the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, there were created in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the first modern legal system, the "new" canon law of the Roman Catholic Church (jus novum, as it was called), and, more gradually, coexisting secular legal systems---royal, feudal, urban, and mercantile. Indeed, the canon law served in important respects as a model for the development of secular legal systems. Later transformations of the Western legal tradition took place under the impact of the eighteenth-century French and American Revolutions, the twentieth-century Russian Revolution, and the crisis of the Western legal tradition in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

The principal purpose of this introduction is to recapitulate, in relatively brief compass, the main themes of the entire work, in order to place the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century transformations of German and English law, respectively, in the context of the Western legal tradition as a whole, from its origins in the late eleventh century, through its successive major transformations, to its precarious situation in twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. It is ultimately from the perspective of the present crisis of the nine hundred-year-old Western legal tradition that the story of its formation and subsequent transformations is to be told.

It may be helpful at the outset to indicate briefly what is meant here by the words "Western," "legal," and "tradition," especially when they are brought together in a single concept, and also by the word "Revolution"---henceforth with a capital R---when applied to the great political and social upheavals that have erupted periodically in the history of the West.

By "the West" I mean the historically developing culture of the peoples of Europe who, from the early twelfth to the early sixteenth centuries, shared a common political and legal subordination, as well as a common religious subordination, to the papal hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church, and who from the sixteenth to the twentieth century experienced a series of great national Revolutions, each of which was directed partly against Roman Catholicism and each of which had repercussions throughout Europe. Included as Western are also non-European nations such as the United States that have been brought within the historically developing Western culture by colonization or, as in the case of Russia, by cultural and political affinity and interaction.

By "legal" I mean the systems of law---including constitutional law, legal philosophy, and legal science, as well as principles and rules of criminal and civil law and procedure---that have developed in the nations of the West since the twelfth century. Despite their diversity in time and space, these legal systems share common historical foundations and common concepts and methods. Also included is what may be called spiritual law, or social law---that is, law regulating ecclesiastical affairs, marriage and the family, moral offenses, education, and poor relief. Prior to the sixteenth century, these were in the competence of the Roman Catholic Church; the Protestant Reformations brought them within the competence of the secular authorities.

By "tradition" I mean the sense of an ongoing historical continuity between past and future, and in law, the organic development of legal institutions over generations and centuries, with each generation consciously building on the work of its predecessors. The historian Jaroslav Pelikan has contrasted such allegiance to tradition with traditionalism: traditionalism, he has written, is the dead faith of the living, tradition is the living faith of the dead. Similarly, one may contrast historicism, adherence to the past for its own sake, with historicity, drawing on the past in building a new future. The sociologist Edward Shils called tradition "not the dead hand of the past but rather the hand of the gardener, which nourishes and elicits tendencies of judgment which would otherwise not be strong enough to emerge on their own. Characteristically Western is the concept of a "body" of law that consciously develops in time, that "grows" over generations and centuries. It is presupposed, in the Western legal tradition, that legal change does not occur at random but proceeds by conscious reinterpretation of the past to meet present and future needs. The law evolves, is ongoing, it has a history, it tells a story. Yet the evolution of law in the West began with a Great Revolution and has been interrupted periodically in the past five centuries by a series of Great Revolutions. Every nation of the West traces its law back to such a Revolution. The interaction of long-term evolution and periodic Great Revolutions is an essential part of the story.

By "Revolution" is meant here a fundamental change, a rapid change, a violent change, a lasting change, in the political and social system of a society, involving a fundamental change in the people themselves---in their attitudes, in their character, in their belief system. This meaning of the word is often dated from the outbreak of the French Revolution of 1789, when the duke of Liancourt brought the news of the storming of Bastille to King Louis XVI at Versailles. "But that is a revolt," exclaimed the king. "No, Sire," said Liancourt, "it is a Revolution." The same word had been applied to the American War of Independence of 1776-1783, and was subsequently applied to the Russian Revolution of 1905 and 1917. It may properly be applied to the English Revolution of 1640, which, however, was called the Glorious Revolution only when it was brought to a conclusion in 1689; to the German Revolution, which was called at the time the Lutheran Reformation; and to the Papal Revolution of 1075-1122, which was called at the time the Gregorian Reformation, after Pope Gregory VII, who initiated it. In each of these six Great Revolutions there was a violent upheaval, a civil war, fought for great ideals. Each required more than one generation to take root. Each sought legitimacy in a fundamental law and an apocalyptic vision. Each eventually produced a new body of law that reflected some of the major purpose of the Revolution. Each of the Great Revolutions transformed the Western legal tradition but ultimately remained within it.

Thus the tradition itself looks not only to the past but also to the future. A slogan of each of the Great Revolutions was "the reformation of the world." The first three---the Paoal, the German, and the English---invoked the biblical vision of "a new heaven and a new earth." The American and the French Revolutions adopted Deist versions of the same---the supremacy of God-given reason, God-given inalienable rights and liberties. The Russian Revolution proclaimed the messianic mission of the atheist Communist Party to prepare the way for a classless society in which all would be brothers and sisters and each would receive according to his needs. The belief systems that accompanied these apocalyptic visions were reflected not only in radical political, economic, and social changes but also in new concepts and new institutions of public and private law.

Thus the story told here of the transformations of the Western legal tradition that took place under the impact of the Lutheran and Calvinist Reformations of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries must be seen as part of a still larger story, in a millennial perspective.

The Origin of the Western Legal Tradition in the Papal Revolution

The larger story begins with the separation of the ecclesiastical and secular jurisdictions, accomplished by a revolutionary movement to free the Church of Rome from subservience to emperors, kings, and feudal lords, and to establish an independent hierarchy of the priesthood, under the papacy, including a hierarchy of professional ecclesiastical courts to resolve disputes and to enforce papal legislation. Led initially by Pope Gregory VII, the Gregorian Reformation, as it was also called at the time, or the Investiture Contest, as it was also called, or the Papal Revolution, as it came to be called in the twentieth century, was marked by civil wars throughout Europe during a period of almost fifty years, from 1075 to 1122. The pan-European Church of Rome became the first modern state. It established a body of law that was systematized in Gratian's great treatise of 1140, characteristically titled A Concordance of Discordant Canons. This was the first modern systematic treatise on an entire body of law, and it was accepted---and still is---as an authoritative statement of the canon law. It was followed in the thirteenth century by authoritative treatise on English, German, French and other systems of territorial secular law.

----

---- 第4章

全米随一の投資家ウォーレン・バフェット自身も、個人投資家はインデックス・ファンドを活用すべきだと主張している。彼は言う。「ほとんどの投資家(個人・機関投資家を問わず)にとって、株式を保有する最善の方法は、手数料の低いインデックス・ファンドに投資することである。手数料やコストを差し引いた後でも、ほとんどの運用機関を上回る成果をあげることができるだろう

Fortune, November 22, 1999.

----

最近の人では勝間和代さんも推しているし、上の引用にもある通り、個人投資家はインデックス・ファンドを活用することで投資を効率化できる、と僕も思う。

また本書第3章の中で、トム・ウルフ(Tom Wolfe)の『ザ・ライト・スタッフ(The Right Stuff)』に言及している箇所があり、読んでみたくなったが、翻訳本は絶版らしく非常に残念だ。

----

小説『ザ・ライト・スタッフ』において、著者のトム・ウルフは「異常な出来事」が「説明不能」の飛行事故を引き起こす様子を描いている。「異常事態」は実は日常茶飯事なのだが、新人パイロットにはこの点が理解できていないのである。

----

以下は、心に響いた箇所。

「親が子供の反抗期をじっと我慢しなければならないのと同じように、投資家もマーケットの乱高下を黙って我慢しなければならないのである」

書名になっている「敗者のゲーム」とは何か?

---- 第1章

「勝者のゲーム」では、勝者のウィニング・ショットにより勝負が決まるが、「敗者のゲーム」では敗者のミスによって勝負が決まる。

----

この意味で、証券運用は「勝者のゲーム」から「敗者のゲーム」に変わった、との著者の主張である。

「プロは得点を勝ち取るのに対し、アマはミスによって得点を失う」と、サイモン・ラモ(ママ)(Simon Ramo)が「初心者のための驚異のテニス(Extraordinary Tennis for the Ordinary Tennis Player, 1977)」の中で指摘しているところからとったらしい。

以下は、巻末のリコメンド一覧

<ライター篇>

1.バークシャー・ハザウェイ(Berkshire Hathaway)のアニュアルレポート

2.ベンジャミン・グレアム(Benjamin Graham)の『賢明な投資家(The Intelligent Investor)』

「弟子だったウォーレン・バフェット(Warren Edward Buffett)が推奨する、唯一の運用関係の本」。

3.ジョン・ボーグル(John C. Bogle)の投資についての著作(参考1,参考2)

ボーグルはバンガードの創始者。

4.デビッド・スウェンセン(David F. Swensen)の『ポートフォリオ・マネジメントのパイオニア的手法(Pioneering Portfolio Management)』

「プロの投資家についてこれまで書かれた最良の書といっても過言ではない」

5.ゲーリー・ベルスキー(Gary Belsky)とトーマス・ギロヴィッチ(Thomas Gilovich)の『人はなぜお金で失敗するのか(Why Smart People Make Big Money Mistakes)』

6.グスタヴ・ルボン(Gustave Le Bon)の『群集(ママ)』

7.フォーチュン誌のアンドリュー・トビアス(Andrew Tobias)の『投資をする前に読むべき一冊(The Only Investment Guide You'll Ever Need)』

「入門書として勧めたい」

8.バートン・マルキール(Burton G. Malkiel)の『ウォール街のランダム・ウォーカー(Random Walk Down Wall Street)』

9.『大投資家の名言(The Investor's Anthology)』

10.クロード・ローゼンバーグ(Claude Rosenberg)の『賢く豊かであるために(Wealthy and Wise)』

「自分の資産を社会貢献に投資することでいかに人生が充実したものになるかを説いている。」

<ジャーナリスト篇>

・ウォール・ストリート・ジャーナル紙のジョナサン・クレメンツ(Jonathan Clements)

2008年4月9日の稿を以て"GETTING GOING"の連載は終了した。

・フォーチュン誌のキャロル・ルーミス(Carol J. Loomis)

・ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のフロイド・ノリス(Floyd Norris)

・フィナンシャル・タイムズ紙のバリー・ライリー(Barry Riley)

・マネー紙のジェイソン・ツヴァイク(Jason Zweig)

Franche-Conte地方(フランス東部)でHenri-Xavier Guillaumeが造るAuxerroisを翻訳家の鴻巣友季子が推すので今度飲んでみようと思った。

「酒質が強く、ミネラル感があり、こんなに標高の高い産地にしては、白桃の蜜のような香りがし、ほろ苦い雑味、ややねっとりしたテクスチュアが、もっと暖かいMaconnaisの(ドライな)Chardonnayか何かを思わせる」(文学界六月号)らしいので。

Auxerroisは、Pinot Blancの変異種。

Henri-Xavier Guillaumeは、元々苗木屋で、D.R.C.やLeroyやGeorge Roumierなどに苗木を卸している。

『カッパドキア・ワイン 銘醸地ブルゴーニュ誕生秘話』(薗田嘉寛 彩流社)は、「D.R.C.のRomanee-Contiを頂点とするCote-d'OrのPinot Noirの苗木は、じつはイスラム教の聖地トルコのカッパドキアから渡来した、という大胆な説のもとに書かれた異色小説」(前掲書)とのこと。

----

答案用紙を走るボールペンが一瞬止まった。ぽたぽたと汗玉が古びた机の木目に落ち、潤って、瞬く間に消えていった。突然、頭のてっぺんから、グラスの底のような厚いメガネのレンズを突き通して自分を見つめる父の視線を感じ、ボールペンがまた走り出した。一九八八年七月、一年で最も暑い三日間に中国の大学統一試験が行われた。大学受験制度が回復されて十年余り、十人に一人という大学の狭き門に駆け込もうとして、ボールペンを止めて汗を拭く暇さえ惜しむ。

----

文学界二〇〇八年六月号に掲載された楊逸(ヤン・イー)の「時が滲む朝」。

第138回芥川賞候補作だ。

楊逸は、1964年ハルピン市生まれ。23歳のとき日本へ留学し、そのまま日本で就職した。

つまり楊は中国人だ。日本語(外国語)で文学を書くなど並大抵の覚悟では為し得ないと思うが、それだけに、我々日本人の興味の的となるのは、楊が満足な日本語を書けるのかどうか、文学と呼べるレベルの日本語を書けているかどうか、だろう。

引用した冒頭部で使われている日本語中、特に違和感を感じるのは、「汗玉」ぐらいか。

論理的に変ではないか?と思うのは、「ボールペンが一瞬止まった」後に「ボールペンを止めて汗を拭く暇さえ惜しむ」と書いている点だろう。たしかに汗は拭いていないがボールペンは止めているのだから、前段の「ボールペンを止めて」は削った方がよいと思う。

ストーリーについては、全体的に古臭さが目立つ。

主人公の梁浩遠は尾崎豊の「I love you」が好きらしく、たしかに世代的にそうなのかも知れないが、僕を含め日本の読者は尾崎豊と聞けば古臭いとしか感じないだろう。なぜ今、尾崎なのか。

偶然にも7/7、日本テレビの『Music Lovers』で、「今」を感じる青山テルマが尾崎の"I love you"を歌った。それでもやはり古臭い。

主人公とその妻との間に生まれた長男の名前が「民生(たみお)」ってのも頂けない。

いくら孫文の三民主義からとった名前だと言われても、日本の読者が連想するのは、どうしたって奥田「民生」でしかない。

また、タイトルの「時が滲む朝」とは何のことを指しているのかよくわからない。

この作を読む限り、この著者が今回、芥川賞を受賞することはないと思った。

When he woke in the woods in the dark and the cold of the night he'd reach out to touch the child sleeping beside him. Nights dark beyond darkness and the days more gray each one than what had gone before. Like the onset of some cold glaucoma dimming away the world. His hand rose and fell softly with each precious breath. He pushed away the plastic tarpaulin and raised himself in the stinking robes and blankets and looked toward the east for any light but there was none. In the dream from which he'd wakened he had wandered in a cave where the child led him by the hand. Their light playing over the wet flowstone walls. Like pilgrims in a fable swallowed up and lost among the inward parts of some granitic beast. Deep stone flues where the water dripped and sang. Tolling in the silence the minutes of the earth and the hours and the days of it and the years without cease. Until they stood in a great stone room where lay a black and ancient lake. And on the far shore a creature that raised its dripping mouth from the rimstone pool and stared into the light with eyes dead white and sightless as the eggs of spiders. It swung its head low over the water as if to take the scent of what it could not see. Crouching there pale and naked and translucent, its alabaster bones cast up in shadow on the rocks behind it. Its bowels, its beating heart. The brain that pulsed in a dull glass bell. It swung its head from side to side and then gave out a low moan and turned and lurched away and loped soundlessly into the dark.

With the first gray light he rose and left the boy sleeping and walked out to the road and squatted and studied the country to the south. Barren, silent, godless. He thought the month was October but he wasnt sure. He hadnt kept a calendar for years. They were moving south. There'd be no surviving another winter here.

When it was light enough to use the binoculars he glassed the valley below. Everything paling away into the murk. The soft ash blowing in loose swirls over the blacktop. He studied what he could see. The segments of road down there among the dead trees. Looking for anything of color. Any movement. Any trace of standing smoke. He lowered the glasses and pulled down the cotton mask from his face and wiped his nose on the back of his wrist and then glassed the country again. Then he just sat there holding the binoculars and watching ashen daylight congeal over the land. He knew only that the child was his warrant. He said: If he is not the word of God God never spoke.

When he got back the boy still asleep. He pulled the blue plastic tarp off of him and folded it and carried it out to the grocery cart and packed it and came back with their plates and some cornmeal cakes in a plastic bag and a plastic bottle of syrup. He spread the small tarp they used for a table on the ground and laid everything out and he took the pistol from his belt and laid it on the cloth and then he just sat watching the boy sleep. He'd pulled away his mask in the night and it was buried somewhere in the blankets. He watched the boy and he looked out through the trees toward the road now it was day. The boy turned in the blankets. Then he opened his eyes. Hi, Papa, he said.

I'm right here.

I know.

An hour later they were on the road. He pushed the cart and both he and the boy carried knapsacks. In the knapsacks were essential things. In case they had to abandon the cart and make a run for it. Clamped to the handle of the cart was a chrome motorcycle mirror that he used to watch the road behind them. He shifted the pack higher on his shoulders and looked out over the wasted country. The road was empty. Below in the little valley the still gray serpentine of a river. Motionless and precise. Along the shore a burden of dead reeds. Are you okay? he said. The boy nodded. Then they set out along the blacktop in the gunmetal light, shuffling through the ash, each the other's world entire.

They crossed the river by an old concrete bridge and a few miles on they came upon a roadside gas station. They stood in the road and studied it. I think we should check it out, the man said. Take a look. The weeds they forded fell to dust about them. They crossed the broken asphalt apron and found the tank for the pumps. The cap was gone and the man dropped to his elbows to smell the pipe but the odor of gas was only a rumor, faint and stale. He stood and looked over the building. The pumps standing with their hoses oddly still in place. The windows intact. The door to the service bay was open and he went in. A standing metal toolbox against one wall. He went through the drawers but there was nothing there that he could use. Good half-inch drive sockets. A ratchet. He stood looking around the garage. A metal barrel full of trash. He went into the office. Dust and ash everywhere. The boy stood in the door. A metal desk, a cashregister. Some old automotive manuals, swollen and sodden. The linoleum was stained and curling from the leaking roof. He crossed to the desk and stood there. Then he picked up the phone and dialed the number of his father's house in that long ago. The boy watched him. What are you doing? he said.

A quarter mile down the road he stopped and looked back. We're not thinking, he said. We have to go back. He pushed the cart off the road and tilted it over where it could not be seen and they left their packs and went back to the station. In the service bay he dragged out the steel trashdrum and tipped it over and pawed out all the quart plastic oilbottles. Then they sat in the floor decanting them of their dregs one by one, leaving the bottles to stand upside down draining into a pan until at the end they had almost a half quart of motor oil. He screwed down the plastic cap and wiped the bottle off with a rag and hefted it in his hand. Oil for their little slutlamp to light the long gray dusks, the long gray dawns. You can read me a story, the boy said. Cant you, Papa? Yes, he said. I can.

On the far side of the river valley the road passed through a stark black burn. Charred and limbless trunks of trees stretching away on every side. Ash moving over the road and the sagging hands of blind wire strung from the blackened lightpoles whining thinly in the wind. A burned houses in a clearing and beyond that a reach of meadowlands stark and gray and a raw red mudbank where a roadworks lay abandoned. Farther along were billboards advertising motels. Everything as it once had been save faded and weathered. At the top of the hill they stood in the cold and the wind, getting their breath. He looked at the boy. I'm all right, the boy said. The man put his hand on his shoulder and nodded toward the open country below them. He got the binoculars out of the cart and stood in the road and glassed the plain down there where the shape of a city stood in the waste. Nothing to see. No smoke. Can I see? the boy said. Yes. Of course you can. The boy leaned on the cart and adjusted the wheel. What do you see? the man said. Nothing. He lowered the glasses. It's raining. Yes, the man said. I know.

They left the cart in a gully covered with the tarp and made their way up the slope through the dark poles of the standing trees to where he'd seen a running ledge of rock and they sat under the rock overhang and watched the gray sheets of rain blow across the valley. It was very cold. They sat huddled together wrapped each in a blanket over their coats and after a while the rain stopped and there was just the dripping in the woods.

When it had cleared they went down to the cart and pulled away the tarp and got their blankets and the things they would need for the night. They went back up the hill and made their camp in the dry dirt under the rocks and the man sat with his arms around the boy trying to warm him. Wrapped in the blankets, watching the nameless dark come to enshroud them. The gray shape of the city vanished in the night's onset like an apparition and he lit the little lamp and set it back out of the wind. Then they walked out to the road and he took the boy's hand and they went to the top of the hill where the road crested and where they could see out over the darkening country to the south, standing there in the wind, wrapped in their blankets, watching for any sign of a fire or a lamp. There was nothing. The lamp in the rocks on the side of the hill was little more than a mote of light and after a while they walked back. Everything too wet to make a fire. They ate their poor meal cold and lay down in their bedding with the lamp between them. He'd brought the boy's book but the boy was too tired for reading. Can we leave the lamp on till I'm asleep? he said. Yes. Of course we can.

He was a long time going to sleep. After a while he turned and looked at the man. His face in the small light streaked with black from the rain like some old world thespian. Can I ask you something? he said.

Yes. Of course.

Are we going to die?

Sometime. Not now.

And we're still going south.

Yes.

So we'll be warm.

Yes.

Okay.

Okay what?

Nothing. Just okay.

Go to sleep.

Okay.

I'm going to blow out the lamp. Is that okay?

Yes. That's okay.

And then later in the darkness: Can I ask you something?

Yes. Of course you can.

What would you do if I died?

If you died I would want to die too.

So you could be with me?

Yes. So I could be with you.

Okay.

He lay listening to the water drip in the woods. Bedrock, this. The cold and the silence. The ashes of the late world carried on the bleak and temporal winds to and fro in the void. Carried forth and scattered and carried forth again. Everything uncoupled from its shoring. Unsupported in the ashen air. Sustained by a breath, trembling and brief. If only my heart were stone.

He woke before dawn and watched the gray day break. Slow and half opaque. He rose while the boy slept and pulled on his shoes and wrapped in his blanket he walked out through the trees. He descended into a gryke in the stone and there he crouched coughing and he coughed for a long time. Then he just knelt in the ashes. He raised his face to the paling day. Are you there? he whispered. Will I see you at the last? Have you a neck by which to throttle you? Have you a heart? Damn you eternally have you a soul? Oh God, he whispered. Oh God.

They passed through the city at noon of the day following. He kept the pistol to hand on the folded tarp on top of the cart. He kept the boy close to his side. The city was mostly burned. No sign of life. Cars in the street caked with ash, everything covered with ash and dust. Fossil tracks in the dried sludge. A corpse in a doorway dried to leather. Grimacing at the day. He pulled the boy closer. Just remember that the things you put into your head are there forever, he said. You might want to think about that.

You forget some things, dont you?

Yes. You forget what you want to remember and you remember what you want to forget.

There was a lake a mile from his uncle's farm where he and his uncle used to go in the fall for firewood. He sat in the back of the rowboat trailing his hand in the cold wake while his uncle bent to the oars. The old man's feet in their black kid shoes braced against the uprights. His straw hat. His cob pipe in his teeth and a thin drool swinging from the pipebowl. He turned to take a sight on the far shore, cradling the oarhandles, taking the pipe from his mouth to wipe his chin with the back of his hand. The shore was lined with birchtrees that stood bone pale against the dark of the evergreens beyond. The edge of the lake a riprap of twisted stumps, gray and weathered, the windfall trees of a hurricane years past. The trees themselves had long been sawed for firewood and carried away. His uncle turned the boat and shipped the oars and they drifted over the sandy shallows until the transom granted in the sand. A dead perch lolling belly up in the clear water. Yellow leaves. They left their shoes on the beach and set out the anchor at the end of its rope. A lardcan poured with concrete with an eyebolt in the center. They walked along the shore while his uncle studied the treestumps, puffing at his pipe, a manila rope coiled over his shoulder. He picked one out and they turned it over, using the roots for leverage, until they got it half floating in the water. Trousers rolled to the knee but still they got wet. They tied the rope to a cleat at the rear of the boat and rowed back across the lake, jerking the stump slowly behind them. By then it was already evening. Just the slow periodic rack and shuffle of the oarlocks. The lake dark glass and windowlights coming on along the shore. A radio somewhere. Neither of them had spoken a word. This was the perfect day of his childhood. This the day to shape the days upon.